Episode 5: Can You Travel Ethically During a Pandemic?

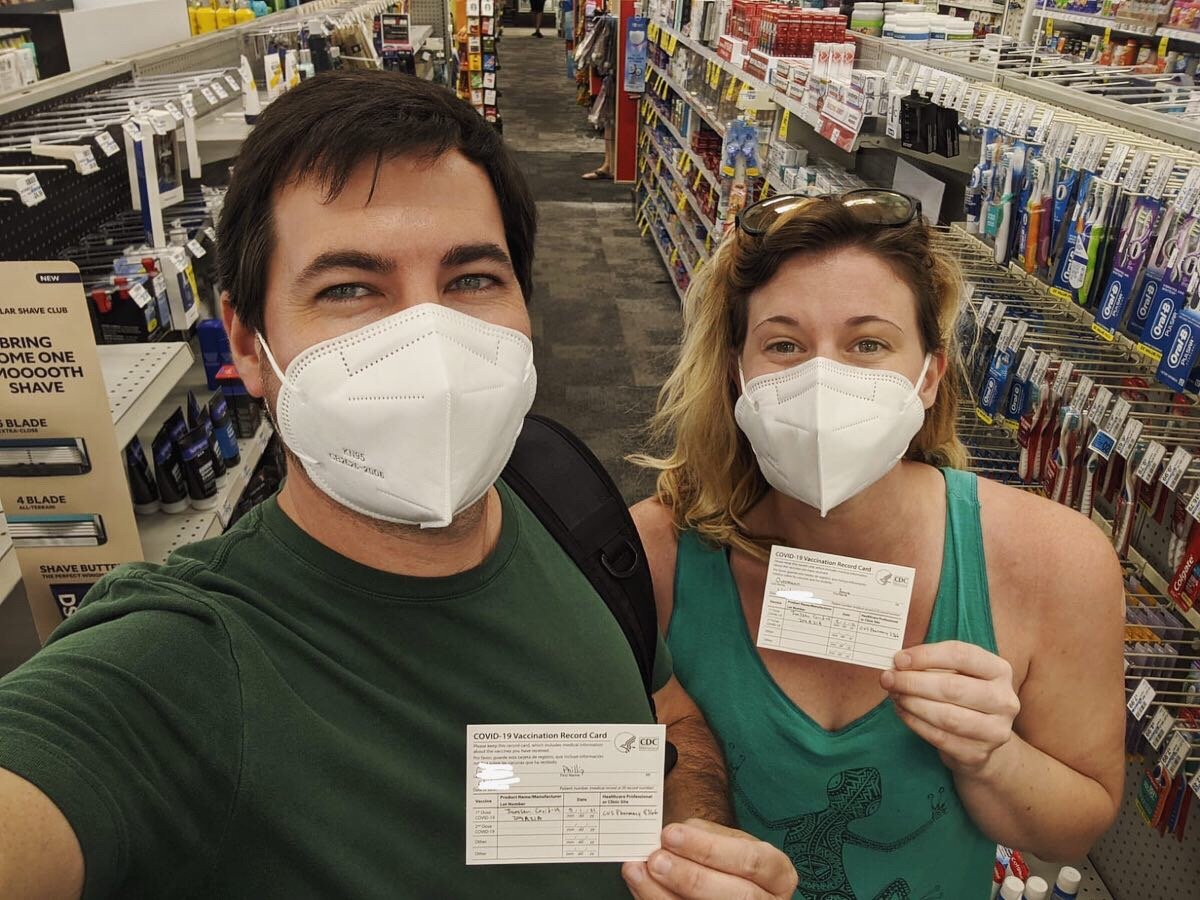

May 1, 2021 in a Phoenix, Arizona CVS Pharmacy: First COVID vaccination (J&J).

In this episode, Anya explores the ethics of traveling during a pandemic. She shares her personal experience, breaks the world into four types of pandemic travelers, and argues for a more humanist approach to international travel.

You can also listen to the podcast on Amazon, Apple Podcasts, Google, or wherever else you listen to podcasts!

Podcast Transcript

Anya Overmann:

Hey everyone. This episode also uses language that some listeners may find offensive.

Enjoy the episode.

-

Outtake

Anya Overmann:

Hi!

Joey Krieger: [laughs]

Evan Clark: [laughs]

Anya Overmann:

Uhhh… okay! [clears throat]

-

[Acoustic guitar music begins playing]

Anya Overmann:

Hi. I’m Anya Overmann, and I’m your host here on The Nomadic Humanist.

Humanist values of secularism, science, and human rights are inherently communal. The Nomadic Humanist explores how individuals without a single fixed home or community live out humanist values.

Through nomadic humanism, we learn to expand the definition of community, building relationships globally across cultures and digital space, to share this one life we have.

In this episode, I discuss whether it’s possible to travel ethically during a pandemic.

[Music stops]

-

A lot of people will tell you that traveling is good for you. There are even studies that support the health, social, and skill performance benefits of traveling. Some of us are obviously so enthused about travel that we have committed our lives to it – like me.

But there’s this misconception that travel makes you a better person – as in, more thoughtful or self-developed. But that’s not necessarily the case. As eye-opening as travel can be, many folks often disregard or do not educate themselves about the ethical concerns that cast shadows on the act of flying to a place you’ve never been before.

A few episodes ago, I discussed the imperialist and other intersectional effects of travel. There are also climate impacts that come from travel. Then, of course, there are public health impacts from travel.

That’s how we ended up with a pandemic: people got sick, they traveled, and facilitated the spread of COVID to every continent. Pandemics don’t happen without the movement of people.

Now, I’m not saying you shouldn’t travel – remember, I’m a person who believes that everybody is entitled to global citizenship.

I’m talking about this so we can travel more ethically. This isn’t to say you have to be 100% perfect when traveling. That’s just not humanly possible. But we should be committed to learning better and doing better.

During this global public health crisis, expert advice has focused on isolating and staying at home. So … does that mean it’s unethical to travel during a pandemic?

… Well, my short answer: it certainly can be unethical, but it has the potential not to be.

-

My partner Phil and I chose to begin my nomadic lifestyle in August 2020 to seek countries with stricter pandemic restrictions. We wanted to be somewhere that took COVID seriously – somewhere we felt safer.

When the pandemic started, I lived alone in South St. Louis City. Even before the pandemic, I didn’t feel safe in that neighborhood. Hearing gunshots every other night, being sexually harassed every time I went for a run or walk, and having smoker neighbors in my apartment building made for a pretty miserable living situation. Then the pandemic began, and St. Louis suffered from both COVID and COVID-deniers. I needed to leave.

So we started our nomadic journey in Croatia because it was one of the few countries open to US citizens and because they had a national mask mandate, which is something that the US didn’t have (nor has ever had at any point during the pandemic).

But what we didn’t know about until we got there was the culture of contempt toward government-mandated COVID precautions.

In the last episode, I talked about how Albania had a rather apathetic approach to public health. In my experience, there was a similar pandemic culture in southern Croatia, where we spent the majority of our time. But up North, on the Istrian peninsula and inland to the capital of Zagreb, people seemed more willing to mask.

Croatia is a young country with a relatively recent history of authoritarianism, so it makes sense that Croatians would distrust the government for restricting their freedoms. But many of those who criticize government-imposed restrictions don’t understand that a pandemic is a public health issue extending far beyond their country's borders. It has had a prolific impact that we will not fully understand until years have gone by and we can study it from a distance.

-

As our travels have progressed, we’ve come to learn that many other travelers don’t consider their impact as much as we expected they would. I thought there would be more digital nomads who care about how they move through the world.

I assumed they saw themselves as I did: a global citizen who wants to treat every place like a home I’d be welcomed back to. But instead, I think a lot of them just see themselves as tourists. Or adventurers. Or some other thing that points to social responsibility being in their blind spot.

There was this one irresponsible nomad we nearly crossed paths with when we were in Albania. He was a friend of a friend who was unvaccinated and being a complete asshole about it over a group chat where we were making plans to meet up.

I remember that Phil tried to give him the benefit of the doubt by asking him what pandemic precautions he was taking in place of being vaccinated. Was he wearing a mask? Was he distancing? Was he sanitizing? That sort of stuff. After all, we were trying to keep the bubble of people we were interacting with as insulated from risk as we could manage, and any bit counts.

This guy responded in this group chat, “Lol. I wash my hands. That’s all. You should spend some time in Ukraine, and you’ll understand what it’s like to live in a place without fear.”

That text really didn’t age well, as Russians started attacking Ukraine just six months after he sent it – but I digress.

After this exchange with this guy, Phil and I pulled ourselves out of all group plans. We didn’t want to spend time with a nomad that reckless (and rude). The other nomads in the group – who were vaccinated – didn’t have enough of a problem with this guy’s approach to set rigid boundaries with him. In fact, there was a preference to avoid the conversation because it was just too stressful.

-

Someone in the group chat replied to his quip about Ukraine with, “Ok guys, can we please please please leave it at that? This conversation is stressing me out, and I’ve really had my fair share of stress these past three weeks. I hope we can respect each others’ decisions regarding whether or not to get vaccinated and trust that each of us is responsible in how we interact with each other.”

Spoiler alert: we couldn’t respect or trust this group of nomads’ judgment, so we opted not to participate.

This is the kind of behavior we have been continuously disappointed by throughout the pandemic from other travelers. The privilege to live as a nomad, or just to be able to travel internationally, comes with more social responsibility, as there are more ethical issues to consider than living in the community you come from.

Few nomads and travelers have learned to champion this heightened social responsibility. Most haven’t even come close. And in terms of the pandemic, I have recognized some interesting patterns in behavior regarding travel and social responsibility.

-

For your understanding and your entertainment, I have come up with four different categories to describe privileged travelers during the pandemic: The Denialists, the Escapists, the Compliant, and the Caretakers.

First, [Anya sighs] the Denialists. These are people who are convinced the threat of COVID is overblown, manufactured, or otherwise unreal. They aren’t vaccinated and seek out places that don’t require vaccination to get in, like Mexico. It’s not that they’re trying to escape the COVID restrictions at home – they were already disregarding pandemic safety. They do not care about the people around them because that’s not their problem. This is their trip, after all, and by god, nobody will mess that up for them. In fact, they’d like to speak to the manager. In. English.

These folks have biiiiiig Christopher Colombus vibes. If this were 1492, they would be sick as a dog on a sailing vessel from Europe to the Americas, about to infect millions of natives and conquer the rest.

But nowadays, they just manifest as the belligerent airline passenger you see in viral videos, and the people commenting on those videos sympathizing with the belligerence. They believe freedom is more important than public health priorities, so it’s highly unlikely they’ll quarantine when they’re feeling sick. They refuse to wear a mask merely out of principle. And their favorite catchphrase is “I don’t live my life in fear.”

-

Next, we have the Escapists. These are people who do the bare minimum for entry into another country. They got vaccinated, but not because it’s the best way to protect themselves and those around them from hospitalization and death. It’s mostly because it’s become increasingly harder to travel without proof of vaccination, and they don’t want to be restricted from traveling. But once they get past border control, they don’t mask up in public or maintain distance unless explicitly asked.

They travel to “escape” COVID, but mostly to escape restrictions. I mean, it’s vacation, and they’re vaccinated – what more do you want from them? They just ... don’t want to have to worry about all that. They’ll comply if asked, but, like, ugh.

They’ll say, “It’s been TWO years already, can’t we just move on?”

Again, other people are not the Escapist’s concern. This is their trip. Whether they follow the science behind it or not, they treat vaccination like a cure rather than a means to reduce your risk of transmitting the virus. And even that risk reduction weakens and needs to be boosted over time.

They are basically like the Denialists, but vaccinated, and will probably put on a mask if you ask them to, but will always be looking for an excuse to take it off. These are the people who let their noses hang out over the top of their masks, like fuckin’ idiots.

Now, the reason for getting a vaccine is certainly less important than the act of getting the vaccine. But only to a point. Because your motivation for getting the vaccine ultimately guides the rest of your pandemic behavior … and it really guides your approach to social responsibility in general. The Escapists do not feel any obligation towards social responsibility.

-

Then there’s the Compliant. These are people who are vaccinated and mask and distance when required but stopped wearing a mask the minute the mandates expired. Their behavior is guided by compliance. They believe the rules are sufficiently safe and are not necessarily able to see how the people making rules, themselves, are not complying with the advice of medical experts as they are pressured by moneymakers and voters who just want things to be normal again without putting the work in themselves.

The Compliant will keep up appearances to a certain point. They want to look like they care. But when nobody is looking or the consequences are negligible, the masks are off. The Compliant won’t necessarily extrapolate how their individual inattentiveness to risk could get them into a dangerous situation. They may justify participation in riskier situations by arguing their compliance with the rules. And when the rules aren’t rules anymore – all bets are off. The Compliant are free and clear to go wild.

While following local rules is important, mere “compliance” as a motivator is not a thorough means for curbing COVID spread – or any other illness – as a traveler. Where the Denialists and Escapists resist social responsibility in the name of their individual freedom, the Compliant rely on lawmakers and rule-makers to fulfill social responsibility. When they are no longer compelled by authority, they do not feel any lingering obligation to social responsibility. They often equate legality with morality.

-

Finally, we have the Caretakers!

Joey Krieger and Evan Clark:

Awwww [beautiful harp noises].

Anya Overmann:

These people go beyond complying with rules to minimize risk as much as they can. They follow the restrictions to protect those around them rather than for the sake of compliance.

While nobody knows how to eliminate the risk of COVID completely, the Caretakers know that minimizing the spread is the best way to move through the world. So they listen to expert medical opinion and err toward caution, especially when traveling. They see vaccines, masks, distancing, and other measures as reasonable inconveniences to care for other people. They’ll definitely quarantine if they feel sick, and they’re willing to alter their travel behavior indefinitely if it means keeping people safer.

Caretakers are folks who are unlikely to cave to the peer pressure of taking masks off in risky situations. They think a lot about those around them and how their presence impacts others. They say things like “this pandemic isn’t over” and “making these sacrifices to protect the most vulnerable among us is worth it.”

Ultimately, they are most interested in minimizing harm and maximizing their contribution to the greater good. They aren’t perfect, but they are open to feedback.

Now it’s important to note – Denialists, Escapists, Compliant, and Caretakers – these are not static categories. We can move between these categories depending on the circumstance.

As this pandemic drags on, it gets harder to be a Caretaker. I have witnessed travelers I know drift from Caretakers to Compliant, or from Compliant to Escapists. It does take a lot of effort to be a Caretaker.

But doing the right thing is seldom, if ever, the easy thing.

[Music break]

-

Before I talk more about committing to being a caretaker as a traveler, I want to take a moment to discuss why we can’t blame the Denialists, Escapists, and Compliant without blaming the system that creates them.

A lot of travel is marketed and framed as what it can do for you. Now, voluntourism is a different story that I will address in another episode someday. But by and large, the advertising language in the travel industry is skewed toward benefitting individuals with money.

“Once in a lifetime.”

“Paradise”

“Feel free again.”

“Live your dreams.”

It’s indulgent kind of language that lacks acknowledgment of the impact of a luxurious travel experience. It helps foster a travel attitude that fails to consider the people who live there.

Then there are these travel/tourism-based companies that try to flout the pandemic and help you find loopholes to travel irresponsibly. This is how the fake vaccine card companies were born.

When you dig into what’s fueling this industry of “it’s all about me” tourism, you unearth the demanding work culture in the US. So many people have minimal vacation days, so they look to eke out the most they can from a travel experience. These unethical tourist businesses play right to that. There is a lot of pressure to enjoy time off, even at the expense of others. It’s hard to blame people for wanting enjoyment during the very limited time their jobs allow them to seek pleasure.

[Music starts]

But this is how we end up with irresponsible travelers.

[Music stops]

-

When I returned to my hometown in June 2021 after about a year of traveling during the pandemic, I entered into one of the most ridiculous pandemic-management systems I’ve encountered in my travels. Less than half of the city was vaccinated, and most people weren’t wearing masks anymore. Signs at the entrances of businesses and public spaces said, “please wear a mask if you’re unvaccinated,” but nobody was checking for proof of vaccination.

It was the honor system. In effect, an “everyone takes social responsibility into their own hands” system. But applying this system to a population of mostly Denialists, Escapists, and Compliant is not an effective means of curbing the spread.

I told my family and friends in St. Louis, “this system isn’t going to work. You guys are going to get slammed with COVID again,” and then … they did. Multiple waves came after.

Can you really expect people operating in such a lackadaisical system to behave responsibly when traveling elsewhere? Not unless they’re Caretakers.

-

Phil and I have worked hard to move through the world as Caretakers. We care deeply about our impacts on public health. We care about how our presence impacts others. Before we decide to travel somewhere, we research COVID case counts, vaccination rates, and mandates. Rather than using local laws as guidance for when to take off our masks, we go off of expert opinion. Expert opinion says it’s safe to go maskless in public once the local, new daily COVID case count reaches 10 or fewer cases per 100,000 people.

We mask in public, including outside if we are close to others, we try to only eat out in the open air, avoid crowds and events, test when we’re not feeling well, get boosted whenever we can, and vet the people we spend time with. Not because it’s the rule but because it’s a calculated consideration of public health risk.

The preventative measures we take frequently exceed what’s locally required, and we feel obligated to do this, particularly as travelers. If we’re constantly shifting to different communities, we should be doing the most we can to prevent COVID spread. Especially because we can afford to.

And perhaps that’s a big reason I struggle to form connections with other travelers. Many of them are Denialists, Escapists, and Compliant. Few of them are Caretakers. I have difficulty getting along with privileged people who don’t consider their impact. They frustrate me.

And hey, I’m far from perfect, and I never will be, but like anyone trying to practice humanist values, I am committed to learning better and doing better, and I am open to good faith feedback on how to fulfill that commitment better. That’s how we practice nomadic humanism.

Because the pandemic is such a whopper of a global issue, we could approach it the same way we approach climate change.

[Music starts]

It’s not something we can change on our own, but we can certainly minimize our impact by being considerate.

[Music stops]

-

Being a Caretaker means that you’re a traveler with the wherewithal to consider your global impact beyond just the context of the pandemic. Caretaking means you recognize that contributing to the greater good is more worthy of your energy than being self-serving and inconsiderate of your impact.

Caretaking means that you recognize your own personal responsibility in the context of social responsibility. It means you understand that your carbon footprint, your public health impact, the way you treat people, what you spend your money on – it all matters. You understand that your impact matters, and you want to take responsibility for it. You want to do the right thing, even when no one is looking. Not because you have to, just because it’s the right thing to do.

And most importantly, you are open to feedback on how you can do it all better.

Because the bad news about the reality of travel is that even as a Caretaker, you still face difficult ethical quandaries. Even when you’re trying your hardest, you will still inevitably end up having some negative impact. Without abstaining from travel altogether, all we can do is work to reduce that impact as much as we can. And that means staying open to sometimes uncomfortable feedback on how to further adapt our mindsets and behaviors to become better global citizens.

-

So I’ll bring back the question I asked at the beginning of this episode: is it unethical to travel during a pandemic?

My answer was: it certainly can be unethical, but it has the potential not to be.

I hope you can now understand how unethical it can be to travel during a pandemic without both consciousness of your impact and application of humanist values in your decision-making.

I hope you can also start to see how this stirs up other questions, like:

Is it ethical to travel by airplane, which has such significant environmental impacts in the face of climate change?

Is it ethical to spend a month living in a city where the cost of living is incredible for you but really difficult for a local?

Is it ethical to rely solely on English everywhere you go?

Is it ethical to take advantage of passport privilege? If so, when does it become unethical?

There are so many more ethical questions to explore around travel. So stay tuned for future episodes that dive into these matters.

-

That’s it! That’s the end of Season One.

[Music starts]

I hope you join me in continuing conversation about nomadic humanism on the interwebs. Yee-haw.

Joey Kreiger: [laughs]

Carly Turro:

Thank you for listening to The Nomadic Humanist, written and hosted by Anya Overmann.

If you enjoyed the show, make sure to like and subscribe to the podcast. You can follow Anya’s journey around the world by visiting nomadichumanist.com.

The Nomadic Humanist is a production of Atheists United Studios and was produced by Joey Krieger and Evan Clark in sunny Los Angeles, California.

Special thanks to Katie Bolton, Phil Gundry, and Heretic House for donating their time and space to the production of this season.

On behalf of The Nomadic Humanist, I’m Carly Turro. Happy travels!

[Music stops]